First Do No Harm ... to the Billing Department

'This needle might hurt ma'am. But it's necessary to suck out all of the money.'

A terrible case has stayed with me of a young woman, married, a mother of small children, otherwise healthy, who out of nowhere developed overwhelming sepsis. As a medical student in Washington D.C., early each morning I would incorporate my hand-written notes into her medical record, kept in a red three-ringed binder at her community hospital ICU.

She was intubated, persistently hypotensive despite vasopressor medications, and her hands and feet were purple. Her left hand was particularly shocking: The small, ring and long fingers were completely black and necrotic. It looked like she’d suffered a terrible burn.

Medical students were discreetly shepherded through her room to see the discolored extremities of profound septic shock. As to the blackened fingers of her left hand — these were held up as a cautionary tale. Rumor had it this was the result of an arterial blood gas (ABG) drawn from the wrist’s radial artery that had gone terribly wrong.

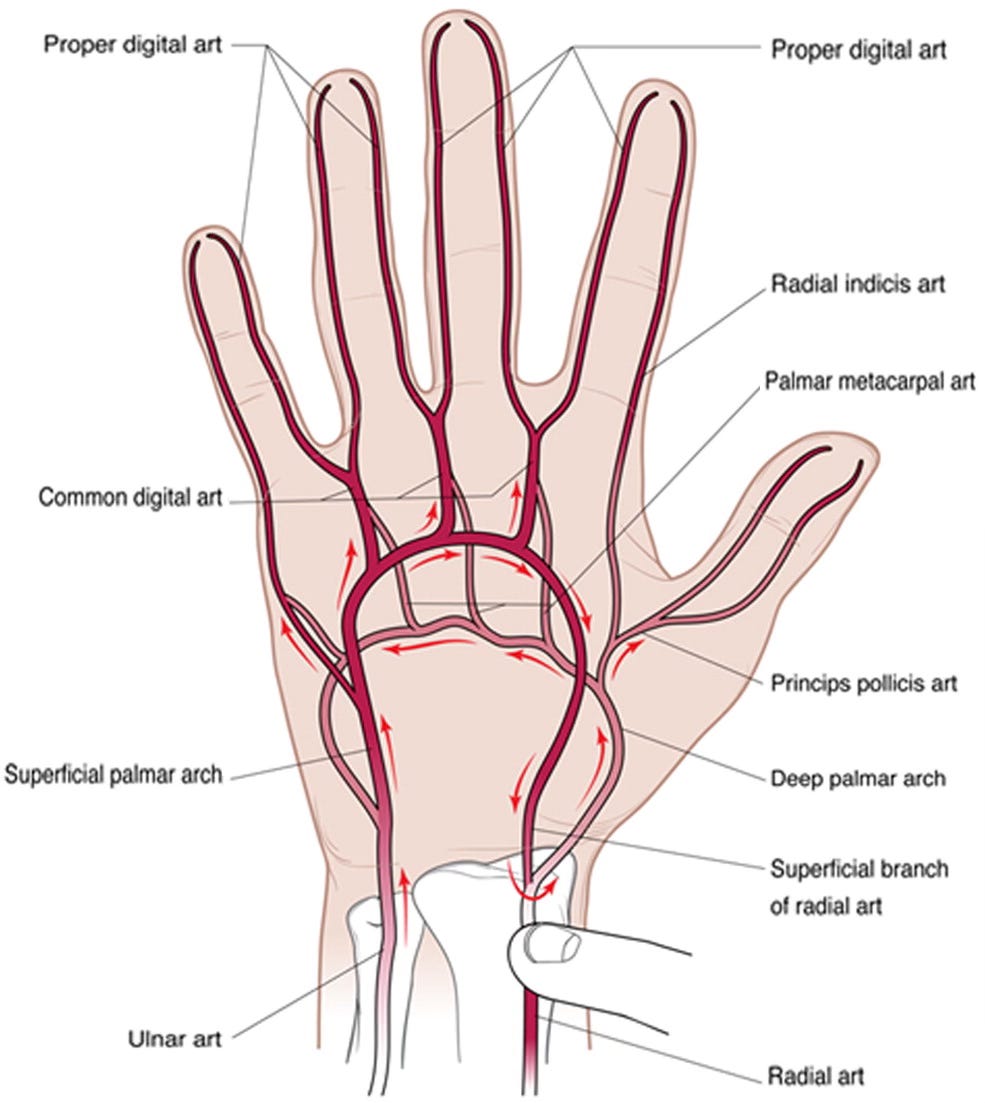

For routine labs, say at a doctor’s office, blood is drawn from a vein. That’s safer, and it’s good enough for almost everything. But in ill, hospitalized patients, if there’s a question about their oxygenation status, arterial blood is sometimes sampled.

Accessing a wrist artery is dangerous, however, so med students are taught to check that the hand will still be OK even if the artery gets damaged or clotted off. There’s a simple test: You squeeze down simultaneously on both wrist arteries, then release one or the other to confirm good blood supply from both sides. Someone, we were told — probably a resident — hadn’t done this prior to the ABG, and then had also injured her radial artery. So now her small, ring and long fingers were turning black and falling off.

This poor woman was actually suffering catastrophic ischemia of all extremities, not just three fingers. But never mind. To us medical students, the explanation that this was someone’s fault felt right.

The patient’s course ground on. Early one morning I arrived, examined her — intubated, hypotensive, mottled, with purple hands and feet, unchanged — and began flipping through that red three-ringed binder. Most of the assessments had a stubborn “hold the course” tone. Remember, she was young, healthy, a wife and a mother, and her illness made no sense. No one wanted to give up.

But there was one unusually brief note. A wise old vascular surgeon had been consulted about her purple extremities. He wrote, in huge, clear letters: “Assuming she lives, I will have to cut off both of her arms and both of her legs.”

It was a watershed moment. The ICU and the family conferred. She was transitioned to comfort care goals, and quickly passed away.

Many things stayed with me. One was that surgeon’s brief, stark note — a demonstration of the power of using simple, clear language to confront uncomfortable facts.

Another was a career-long wariness of the ABG. Which is why it distresses me that ABGs seem to be coming back into vogue. We’ve needed them less and less in recent years, thanks to improvements in medical knowledge and also to the availability of non-invasive alternatives. The ABG had seemed to be relegated only to select ICU cases. But suddenly, we in the ERs are being asked to perform them more. Only now, it’s not always about providing better patient care; sometimes, it’s about helping the hospital bill more.

Other People’s Money, Other People’s Fingers

I’ve done my share of accessing the radial artery. It certainly seems painful. Patients who have easily tolerated a central line to the jugular vein — involving a large needle in the neck — often squirm and moan in response to a small needle in the wrist. Otherwise obtunded patients will sometimes pull away from an ABG. Apparently, the body doesn’t like sharp metal digging around in the arteries.

Painful, yes, but are ABGs truly that dangerous? This has been poorly studied, but researchers in Denmark recently provided some answers. They reviewed 473,000 ABGs performed over 10 years at their three-hospital system, and identified 669 “major complications”. They defined “major complication” as something that led to “prolonged hospitalization time or a need for surgical treatment or another intervention.” So, these are not just hematomas that are ice-packed and resolve; this is more in the “fingers turn black and might fall off” spectrum.

This works out to 1.4 complications for every 1,000 ABGs. The researchers concluded: “Arterial punctures for arterial blood gas analysis are safe procedures.”

Sure, agreed. Assuming you have to do ABGs — hold that thought! — then this data suggests it’s going to be safe 998 or 999 times out of 1,000.

But if you do a gazillion ABGs, suddenly this math doesn’t seem so favorable. Look again at the Danish experience: 669 major complications over 10 years. That’s about 67 “maybe this hand is going to fall off now” events every year at just their three hospitals — more than one per week!

Meanwhile, even as we have reflexively stuck lots of needles into lots of arteries over the years, the questions we ask with a blood gas — acid-base pH status, oxygen gas levels, CO2 gas levels — can often be reliably answered now in safer, less painful ways.

Oxygen levels are, for most situations, well assessed by non-invasive finger pulse oximetry. Venous blood gases (VBGs) can answer the rest — and adding a VBG into the venous blood tests already being drawn logically adds zero pain or risk. No one’s fingers ever fell off after a VBG. Studies have shown VBGs can reliably track the pH in diabetic ketoacidosis, and the pCO2 in decompensated Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. A study published in March looked at 250 emergency department patients suffering from various critical illness, and found good correlation between ABGs and VBGs on everything except for oxygenation (which, again, is read by the pulse ox blinking cheerfully away on the patient’s finger).

Yet even as the literature supports less and less routine need for an ABG, I’ve more and more often been told that “the hospital” now needs an ABG on this respiratory patient. It’s “protocol.”

Why? Well, why does “the hospital” ever want anything?

That’s right: It’s about billing.

“By now, most facilities have experienced many claim denials regarding the assignment of code J96.XX for acute respiratory failure,” reports an October 2020 article in For The Record, a publication for healthcare billing and management.

When a patient is admitted for asthma or heart failure, it turns out that tacking on the three-word additional diagnosis of “acute respiratory failure” can almost double the reimbursement. Wow! But by the insurance rules, that diagnosis requires at least two of the following three criteria: low oxygen levels, high CO2 levels, and / or “signs and symptoms of acute respiratory distress.”

The ABG alone often gets you two out of three, and then you don’t need the doctor’s help to double the hospital’s bill. But without the ABG, one needs a low oxygen level on a pulse oximeter and a well-written physician chart. Good billing documentation calls for a lot of prose — the doctor has to vividly describe a patient with rapid breathing, difficulty speaking, wheezing, etc. — and if patients don’t have that, or physicians don’t document it, billing is out of luck.

From the hospital’s point of view, this is easy: Just get an ABG. That’s how you make the billable diagnosis! There’s a lot of money at stake! The doctor may not need the ABG to guide her care. But the doctor also can’t be trusted to provide 100% compelling word pictures of every admitted dyspnea patient. In the upside-down world of modern American medicine, it thus makes perfect sense to subject the patient to a medically unnecessary, painful and occasionally dangerous procedure, so we can incrementally increase our chances of successfully charging them more.

Excellent piece of writing. Thank you.

Thank you for your insights.

Modern American medicine has been destroyed by the same pathology that has destroyed American society. Socialism, and its incestuous relationship with the Insurance Industry, hopped up on the steroid of government mandates and the ACA, have turned this gift to mankind into Frankenstein's monster.