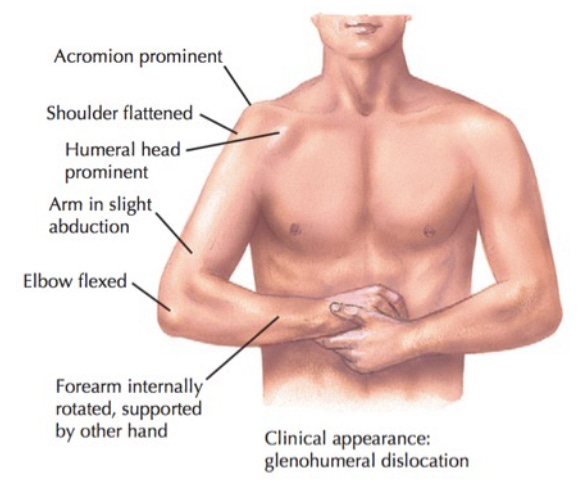

The patient was moaning and swearing, his emergency visible from across the department: the flattened shoulder, the dent where the humeral head used to be, the bulge below the clavicle where it was now. The paramedics had made a sling from a triangular muslin cravat, but he wasn’t using it: with his good left hand, he clutched his right to lift that injured arm out of the sling, holding it in elbow flexion, a little away from the body, with the forearm internally rotated.

The patient told me how it had all happened, and I told him what he already knew.

“Looks like you dislocated the shoulder,” I said.

He and I agreed we ought to put it back.

Enter the ritual paperwork.

“So we have a formal consent process — ”

“I consent,” he replied.

The nurse offered him a form and a pen. He gave her an exasperated look, nodding at his whole situation.

“Sure, we’ll sign it for you.”

As I spoke, we cut off the sling the paramedics had applied. I sat down on the edge of the bed facing him, and cajoled him into releasing that left hand’s death grip on the right.

“Wait, wait, wait!” he yelped. But I kept moving his arm, talking right over top of his refusal.

“I’m just going to put your right hand on my right shoulder, and I’ll stop there,” I said.

He watched wide-eyed as I transferred his hand to my shoulder, locking it there with my left hand, and then draped my right forearm in the crook of his elbow as a hanging deadweight.

“I’m not doing anything,” I lied. I was already into one of my favorite reduction techniques.

“Don’t do anything yet, doc!” he said. “I’m going to need something for the pain!” (EMS had already given him IV fentanyl.)

“Sure, we’re not going to do anything crazy,” I replied evasively.

The patient anxiously asked if he could be sedated. I pretended not to hear it, and asked him to again recount how this had happened, and I continued to ever-so-slightly manipulate the shoulder.

Some dislocations do require heavy sedation, but most respond easily to a gentle touch. Patients all say they want sedation, but most don’t understand the implications of that. Because sedation requires more nurses, more monitors, extra paperwork, and of course the sedative medications themselves from the pharmacy or the ED dispenser, it takes time to organize. So, the patient who “needs sedation” will sit in excruciating pain for at least an extra 15 minutes. If a more critically ill patient arrives or decompensates in the interim, that purgatory stretches far longer. I’ve seen a shoulder dislocation that I might have easily reduced in the first two minutes instead wait in agony for two hours while critical patient after patient butted in line ahead.

What’s more, for most shoulder dislocations, we don’t really need a shoulder x-ray. But if we’re going to be waiting anyway? Well, then let’s get a shoulder x-ray! The customer patient getting an x-ray thinks this is progress, and is much happier than the patient just sitting there in pain, waiting.

And yet the upfront shoulder x-ray is often of questionable value. Usually it just runs up the bill, draws out the delay, and increases the discomfort involved. The x-ray techs have to move the arm to get the pictures; this is painful, and some shoulder dislocations “spontaneously reduce” at x-ray. All others return from the x-ray in worse pain than ever, and wait again, until the care team can recoalesce and rally for the final effort.

After sedation, patients are groggy, foggy, and often nauseated. They generally lose at least an extra hour lying in an ED (and tying up a bed). So it’s better for everyone if the shoulder can be coaxed home up front, without drama.

“We’re just going to rest here like this” — facing each other, his right hand gripping my shoulder, the bent elbow like a hammock for my lazy arm — “and I’ll tell you what happens next.”

Enter the informing and consenting:

I don’t think the shoulder’s broken, though it could be, but even if we x-rayed it and found a fracture we’d try to reduce the dislocation the same way; we might succeed, we might fail; if we pull too hard even an unfractured arm might fracture (that never happens, but I have to mention it), the nerves might get injured or even already be injured, and if we can’t reduce it easily, you might need sedation —

“Great, knock me out!” he interjected.

— with a sedative, you might have an allergic reaction or get oversedated and stop breathing, although we know how to handle all that and it never happens, though it might, just like it’s theoretically possible you could die (which also never happens) —

“I get it, no guarantees,” he said.

Against his will, he was starting to relax, overcome by my droning. I reminded him to sit up. I let gravity pull steadily down on my arm draped over his elbow. I massaged his trapezius, deltoid, and biceps muscles.

“It’s not like I have an option anyway,” he groused. “What am I going to do, walk around hunched over like an ape, with my arm dragging on the ground — ” and then he sighed in relief, as the shoulder clunked into place.

‘What is wrong with doctors?’

Some time later, a new patient popped up on my computer. Even as I clicked on her name, the chief complaint of “Seeking prescription refill” was amended to “High blood pressure.” During her 45-minute wait, she’d had blood pressures of 210/105, 190/100, 200/95.

Her chart said she was in her 50s with no medical history and no primary doctor. The only notes were from an encounter a month ago, for a foot injury, when my ED colleague had noted similar high blood pressures and referred her to a new primary care provider. I assumed she’d been unable to keep the appointment and was back hoping we’d just prescribe blood pressure medication.

I was half right. She still had no health insurance or regular doctor, but she had just been to an occupational health clinic. That clinic had prescribed Hyzaar DS®, a brand-named antihypertensive combining two ancient generics, losartan 100 mg and hydrochlorothiazide (HCTZ) 25 mg, into one pricey pill.

But when she went to fill this prescription, the pharmacist told her a month’s supply would cost $90. Or $1,080 a year. All out of pocket.

She was not optimistic I could help. But in despair, she’d paid for one more $150 ED visit to find out.

I returned to my computer and called up a website that has coupons for prescriptions at big chain pharmacies. By splitting the brand-name losartan–HCTZ pill into its generic components, I got the monthly price down to $6. I printed two generic prescriptions, with the associated coupons, and returned triumphantly. I expected a hero’s welcome. But I also wasn’t surprised to find her mostly just indignant.

How could a medication that cost $90 a month now suddenly cost $6?

How did that make sense?

What was wrong with doctors?

Well, I explained lamely, everybody has different insurance, so we doctors don’t always know the cost. Maybe the other doctor assumed a combination pill would be convenient?

“Convenient!”

So the first doctor didn’t inform her she could pay $6 a month, and assumed she’d find the dubious convenience of two pills pressed together into one pill worth an extra $84 a month? “You don’t think she should have told me my options?”

Actually, I do. In fact, I believe that any physician who wants to prescribe any brand-name that simply combines two old generic medications should have to obtain the patient’s formal, written consent — complete with a formal review of other options.

A few years ago, a pharmacy asked me to pay $800 for a family member’s acne medicine, Onexton®, which combined a topical antibiotic, clindamycin 1.25%, with benzoyl peroxide. A similar-sized jar of generic topical clindamycin 1% was $10. I changed the prescription, paid $10 — instead of $800! — and picked up a benzoyl peroxide face wash on my way out.

It felt like cheating, that with my doctor’s prescribing authority (and knowledge of how little difference there is between a cream with 1% or 1.25% of an antibiotic in it) I could so easily fix this for myself, while every other American would have had to either pay $800 or go without.

Mindless rituals

We in medicine claim to have such deep respect for patient autonomy that we ritually inform people with acute orthopedic injuries of the obvious: that the injury and stabilization efforts may have consequences.

We delay their treatment for this celebration of the self-evident, culminating in the ceremonial signing of a document no one has read.

But in an era when medical bills bankrupt hundreds of thousands of families each year — when Nobel laureates sell their medals to pay their doctors, and young people die trying to ration their over-priced insulin — we still routinely prescribe combined medications that we must know by now will cost patients 10 times as much as the separate components.

And when patients ask, “What will this cost?,” we shrug helplessly.

This happens every day throughout the country — doctors mocking the very idea of patient autonomy and informed consent, as we inflict easily avoidable and potentially catastrophic financial harms. It gives the lie to our sworn pledge to do no harm.

An earlier version of this article appeared in The New England Journal of Medicine.

I just love reading your stack, Matt. Always informative, most often infuriating -- only because we all know the system is broken. Or "incoherent," as you aptly put it.

Knowing that there are doctors like you out there gives me hope.

Medical schools churn out clones who memorize the answers and bed side manner is no longer taught. Most Drs. wind up in groups who are owned by either a hedge fund or private equity or part of a hospital because of that they can only spend at the most 15 minutes with each patient (customer). Everything is a transaction. Drug companies give out “bonuses” to the good Drs. who prescribe the “new” drugs which are like you mentioned old drugs combined into one new one and given a fancy name which patients (customers) can recall by the dance number from TV. If said drug isn’t on the pharmacy benefit managers list that makes them the most money you’ll be rejected or need a “prior authorization” for people who have zero medical education whatsoever but are in charge of your medical care and outcome. Most Drs. will bow to these asshats instead of drawing up the required authorization as that takes up more of their time as they try to keep on schedule seeing as many customers as possible daily. It’s all a fucking grift anymore. We spend the most on healthcare than any nation on the planet and have not only the worst outcomes but our life expectancy has shrunk which means we are living less time on the planet than other people living in any other nation on earth. Shit needs to change and it needs to change fast. Stay away from hospitals they will kill you in them.