Dear readers: A quick note to say I have not been charging paid subscribers since mid-summer, when I froze all Substack payment collections. I’m going to leave it like that for now — so, no one is getting charged. I like it better that way anyway: I have a full-time day job, and I only want to take anyone’s money if I’m writing often enough (and well enough) to feel I can justify it. That said: A huge thanks for the humbling votes of confidence of a paid subscription! (And a nod of thanks to Substack itself: it is great that they even allow an indefinite pause in everyone getting paid).

Right now, we spend more money on Pfizer’s Paxlovid™ than on any other oral medication in the world.

There are injections that cost more, but when it comes to pills, the antivirals nirmatrelvir-ritonavir — when marketed specifically for COVID-19 — literally cost twice their weight in gold. (A gram of Paxlovid™ costs $132, while the Internet today says a gram of gold costs about $59.)

Pfizer reports Paxlovid™ brought in $18.9 billion last year. Only the company’s COVID-19 vaccine earned more: almost twice that, at $37.8 billion. Between the vaccine and the Paxlovid™ pills, Pfizer had its best revenues ever last year, raking in more than $100 billion.

The price tag for a 5-day course of Paxlovid™ is $530. That’s a “pandemic special” though — proudly negotiated by the White House as a bulk purchase of millions of doses — and the price may well go up this winter, just as the government stops picking up the tab.

For comparison, a 5-day course of the generic antibiotic azithromycin, which actually does work, usually costs less than $10. If you want to be fancy and get the brand-name Zithromax® Z-pak, it’s still less than $20.

Consider again that gold-plated, $18.9 billion take. Paxlovid™ had better be an amazing medication, right? (Spoiler alert: It’s not.) After all, our government just spent a lot of money on it.

For context, the Biden Administration initially talked of making community college free to all Americans, but then backed away over the estimated price tag of about $9 billion per year.

So Americans can’t have tuition-free community college. But we can spend more than twice the cost of that on “meh” efficacy anti-viral pills? (We can also apparently divert 12 times the cost of “community college for all” to the project of demolishing / rebuilding Ukraine. But no free community college for you — that would be expensive!)

Back to Paxlovid™. With the public now bored by COVID-19, sales this year will fall, but industry analysts predict Paxlovid™ will still bring in worldwide revenues second only to COVID booster shots, and to a couple of life-changing therapies: Keytruda® (pembrolizumab, a chemotherapy for cancer treatment) and Humira® (adalimumab, an injectable immunosuppressant, used for autoimmune disorders).

The push to prescribe Paxlovid™ as widely as possible is underway. Pfizer’s “Know Plan Go” campaign seeks to convince the public they are a high-risk case if they catch COVID-19 and also have, say, ADHD, or are “overweight,” or even — God forbid — indulge at times in “physical inactivity.”

Meanwhile, even though Pfizer wants you to start Paxlovid™ right away if you’re older than 50 (!), the scientific evidence doesn’t really support that. In fact, nirmatrelvir-ritonavir only has evidence for a specific, and shrinking, population: high-risk, unvaccinated, and COVID-19-naïve patients.

The original study establishing nirmatrelvir-ritonavir as a useful COVID-19 therapeutic, published two years ago in the New England Journal of Medicine, reported that starting nirmatrelvir-ritonavir within five days of infection prevented hospitalizations and deaths among patients with high-risk co-morbidities ranging from obesity (80 percent of those enrolled were obese) to hypertension and cancer.

This double-blind, placebo-controlled trial enrolled 2,246 patients around the world. There were 9 hospitalizations and no deaths among the 1,039 treated with nirmatrelvir-ritonavir, versus 67 hospitalizations and 12 deaths among the 1,046 treated with placebo.

That worked out to preventing one death for every 87 high-risk patients, and one hospitalization for about every 18 such patients. It sounded pretty good.

But this was during the height of the virulent Delta variant; the study excluded anyone who’d received a vaccine; and in fact it excluded anyone who’d ever had COVID-19.

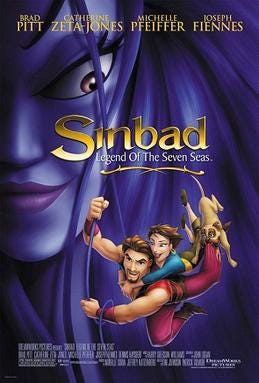

Fast-forward to today. Successive waves of the coronavirus have swept the planet. Mutation has led to progressively more contagious but less virulent strains, from Alpha to Delta to Omicron to, now, “Eris.” (We’re really calling it Eris, after the Greek goddess of strife and discord? The Michelle Pfeiffer-voiced villain in the Dreamworks “Sinbad” movie? What’s the thinking here?)

Will Paxlovid™ be of much use this fall or winter? After all, almost everyone has some immunity thanks to vaccinations, prior infections, or both, and the dominant circulating coronavirus strains (so far) are quite mild.

A study published in Annals of Internal Medicine several months ago is pretty revealing. Researchers used the medical record of Mass General Brigham’s healthcare system — which includes hospitals and medical practices across Massachusetts and New Hampshire — to identify 12,541 older patients who contracted COVID-19 in early 2022, had high-risk comorbidities, and were treated with nirmatrelvir-ritonavir.

More than 90 percent of these Omicron-era patients were vaccinated, and a prior COVID-19 infection was not among the exclusion criteria. The authors matched their treated patients against 32,010 similarly high-risk patients with COVID-19 who did not get Paxlovid™.

The first thing to note: This was not the Alpha or Delta era, when COVID-19 was truly lethal for many, but the far milder Omicron era. Not surprisingly then, “hospitalization or death” in the entire study set was low, only about 1%. Readers savvy about how “combined endpoints” work in research papers can already sense that this 1% result is all driven by “hospitalization”; and in fact deaths within 28 days across the entire study were only about 0.1%.

In other words: 99% of the highest-risk patients shrugged off Omicron-era COVID-19 without even needing a hospital; and 99.9% survived it.

Is this situation truly where we want to focus more money and effort than on any other oral medication in the world?

If the answer is yes, then the Mass General Brigham data suggests getting nirmatrelvir-ritonavir might help: Hospitalization or death occurred in 0.55% of those treated versus 0.97% of those not treated. Again, this was almost entirely about a decrease in hospitalizations, with an absolute difference of 0.4%.

As Dr. Mike Menchine calculates at the indispensable Emergency Medicine Abstracts, that equals a Number Needed to Treat (NNT) of 250: Give 250 patients the medication, prevent one hospitalization.

He does more back-of-the-envelope math: 250 courses of Paxlovid™ at about $500 each equals $125,000. That’s the price-tag associated here with preventing one hospital admission.

As a practicing ER doctor I can tell you that in the Omicron era, a lot of patients with a cough and some co-morbidities — real co-morbidities like kidney disease, heart disease, etc., not Pfizer’s scary wishlist — get hospitalized for an uneventful stay and a discharge next morning. The logic is: “Let’s just bring her in and watch her for the night, she’s pretty old and she has COVID.”

What about preventing one death? Menchine just shrugs and says it would involve prescribing “many thousands” of courses of Paxlovid™. I agree, and it certainly cost multiple millions of dollars in gold-plated Paxlovid™ to prevent a COVID-19 death in this Mass General Brigham data set.

Remember, this is what the crude math looks like when Paxlovid™ gets offered judiciously, only to the truly high-risk, and at the government’s $530 bulk discount.

This winter, however, every American who has been told they have a “mental health condition” — whatever that might be — or who “struggles with their weight” like the musician and Pfizer spokesman Questlove — or has enjoyed the guilty pleasure of “physical inactivity” — is being exhorted “to have a plan” for the non-event of a mild COVID illness. And that plan is supposed to involve starting soon-to-be-pricier Paxlovid™.

What’s the cost to society? What will happen to insurance premiums? Will patients have to pay out-of-pocket? I well recall several years ago being outraged on behalf of my patients when they would catch influenza, be prescribed Tamiflu® (oseltamivir) — another gold-plated anti-viral of questionable medical value — and have to pay $75 out-of-pocket at the pharmacy despite having health insurance.

My personal plan for Paxlovid™ is to mostly ignore it. I will try to follow the World Health Organization recommendations, and reserve nirmatrelvir-ritonavir for the very highest risk, unvaccinated patients (especially if I come across a COVID-naive unicorn). The Mass General Brigham data suggested Paxlovid™ reduced admissions and deaths among the specifically unvaccinated, high-risk patients by about 2%. That’s a Number Needed to Treat (NNT) of about 50 — or about $25,000 to prevent a hospitalization, and probably 10 times that cost to prevent a premature death.

Matt Bivens, MD, works at emergency departments in Massachusetts, including St. Luke’s in New Bedford and Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston. An earlier version of this article was published in Emergency Medicine News.

Great column. Wish you could get it printed in NYT or other msm.

Hi again, I'm just looking at the paper. Adverse events were dismissed, though they were about 22% in both groups. I can't find what the placebo was- it says it was a 'matched placebo' or a 'placebo for ritonavir q12h'?? The AZ trial used the meningitis jab as placebo - a common way to hide adverse events.

Also the paper only seems to refer to 'covid' deaths. It mentions that the viral load also dropped in treatment arm. If ritonavir is as powerful and oxidising agent as say AZT then the genetic sequences that indicte a positive for 'covid' or 'covid death' may well be mutated, altered and reduced and the patient less likely to test PCR positive. This has nothing to do with indicating that there are less deaths overall or that the drug is doing the patient any good at all.