Spilt Milk and Other Catastrophes

Working in a hospital teaches the lesson that every mistake can happen. There are no mistakes that can't happen simply because they would be too absurd, or the consequences too terrible.

A patient who had just arrived by ambulance hopped off his emergency department hallway stretcher, handed my colleague his two upper front teeth, and walked out.

My colleague — I’ll call her “Claire” — had some questions.

Like: Should that guy be allowed to leave? (He had been transferred from a psychiatric hospital, where he’d just been punched in the face.) Also, would he be coming back for his teeth? Also, what was she supposed to do with these teeth? (Eww!)

I took a break to grin and to brainstorm. Avulsed teeth could be stored in saline or milk, and wasn’t there also a special solution? Yes, the Internet replied, Hank’s salts, a bicarb-heavy concoction used for cell growth media. We didn’t have that.

Claire chose milk, and then wandered off. That’s how I ended up sitting next to a green plastic denture cup filled with dairy and teeth. I was deep in the paperwork that plagues the psychiatry-side of our ED when a new colleague arrived. I’ll call him “John.”

John asked: Are these somebody’s dentures?

He lifted the plastic container aloft in query. It came open, and milk and teeth flew all over me. Milk beaded on the keys of my computer. It soaked the federal government paperwork we have to fill out for every transfer, and the pink-paper psych holds I’d just signed.

John was horrified and apologetic. But my cry of accusatory ire was: “CLAIRE!” After all, if you want milk and teeth thrown all over someone, leave a hidden cup of milk and teeth next to them.

(Side note: Two days later, working the same shift, I met Claire’s source patient. He needed to get his head on straight, he said, with an apologetic, gap-toothed smile. He was making bad choices. I agreed. “Yeah you are!” I said.)

Set up to Fail

John’s shift was about to get worse. A gentleman in his 50s with a history of occasionally going into an irregular heart rhythm had flipped back into it. He wanted John to cardiovert him: Basically, to put on the electric pads and shock him out of atrial fibrillation and back into a normal heart rhythm. This is indeed something we often do in medicine. It usually works fine.

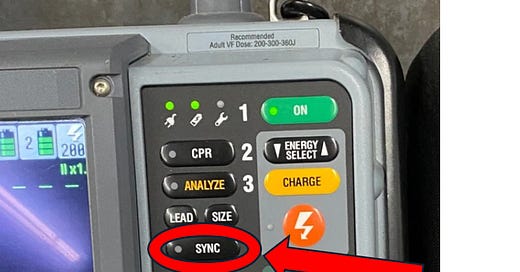

John talked to the Cardiology service to make sure everyone agreed with this plan. Consents were signed, the patient was given some sedation, and John himself managed the monitor / defibrillator. To start, he pushed the synchronize button.

In a synchronized cardioversion, the machine times the shock — synchronizes it — so that it lands right on top of the next heart beat. In EKGspeak, it drops the electricity right onto the R wave:

Once John hit the sync button, the machine put a little arrow over each QRS complex to show it was paying attention. John then pushed the shock button, and after a nanosecond or so of pause, the machine saw its R wave target and fired away:

The first shock didn’t work: The patient was still in atrial fibrillation afterwards. That’s not unusual. Sometimes it takes escalating doses of electricity. So, John dialed up the joules a little higher and tried again.

But this time, he failed to hit the sync button.

(The operating manual says the LIFEPAK 15 can be set to stay in synchronized mode once that’s selected, or to default back to unsynchronized. Hospitals and ambulances across the nation use these same machines. But from machine to machine, some need “re-synchronized” each time and some don’t. What a design flaw!)

John pushed the shock button and the unsynchronized result was catastrophic. Electricity landed not on the R wave, but at the end of the T wave.

The patient went into a ventricular tachycardia cardiac arrest:

After two frightening minutes, involving chest compressions and two more defibrillations, the patient’s pulse came zooming back. Minutes later he was sitting up and, by all accounts, more upset to still be in atrial fibrillation than about having briefly been struck dead. He urged John to have another try. But John was spooked and had had enough. The patient was admitted, and had an in-house cardioversion the next morning.

Cue the root cause analysis of our latest Never Event.

Some asked why we were even doing a non-emergent cardioversion in the ED. (I would have done it. I’ve cardioverted patients many times. It’s safe (usually), it’s fun, it was what the patient and Cardiology wanted, and not having to admit a patient is good for all involved). Others critiqued the joules John had selected (I would have used more electricity up front). Still others asked why the doctor was running the monitor / defibrillator, when in our hospital that’s usually a nursing task.

Me, I blamed Claire.

Well, her and the Physio-Control corporation. Why, I asked, doesn’t their LIFEPAK always default to trying to synchronize? No matter what the cardiac rhythm is — even if it’s ventricular fibrillation, which has no QRS to synchronize with — the device could wait a couple of seconds, trying to synchronize with something. Colleagues put forward engineering-based arguments for why that wouldn’t work, but I remained unconvinced. And not just because I always like to blame a corporation.

The Sync Button and the End of the World

As the playwright Anton Chekhov famously observed, if you open a short story or play with a rifle hanging ominously on the wall, then sooner or later the rifle has to be fired — that’s the expectation. This is not just a literary convention, but a reflection of how reality itself works. Catastrophic failures hide in plain sight, like Chekhov’s gun hanging on the wall, awaiting the moment they can move from potential to actual. If you hide a cup of milk and teeth next to someone’s desk — it will eventually be spilt. If your work flow involves an unobtrusive button that must be ritually pushed — then sooner or later you’ll fail to observe that ritual, and someone will ritually die. At least briefly.

A man I knew who would have agreed with this was the inventor of the “synchronize” button himself.

Dr. Bernard Lown, a Boston cardiologist, is “credited in the Western world with initiating the modern era of cardioversion,” according to a 2023 journal article. He was in his 90s when I met him (he passed away three years ago at the age of 99). In the 1960s, he had founded Physicians for Social Responsibility (PSR), a Boston-based peace group, and in the mid-2010s I had taken over his role there. So, we had things to talk about.

During the Cold War, Lown had used PSR to link up with like-minded Soviet physicians. The resulting umbrella group won the 1985 Nobel Peace Prize. Lown had co-accepted the Nobel medal in Oslo, and more than 30 years later, over coffee at his home, he proudly showed it to me.

A cardiologist like Lown could make common cause with Soviet doctors back then because the Russians were leaders in the cardiac resuscitative sciences. They had not only launched the first satellite and then put the first man into space — Sputnik in 1957, and Yuri Gagarin 1961 — but also put the first portable, out-of-hospital defibrillators into the hands of paramedics.

In the United States back then, defibrillators were enormous, bulky things, and had to be wheeled into a room and plugged in to alternating current (AC) wall outlets. The far-smaller Soviet defibrillators had been designed by Dr. Naum Gurvich. He preferred direct current (DC), which could be discharged from a battery and was felt safer for the myocardium.

Lown studied the medical findings of Russians, Americans and Europeans across decades of study. In particular, he studied years of animal experiments by others: the hearts of thousands of anesthetized dogs had been shocked into cardiac arrest, then shocked back out of it.

As a dog-lover I cringe. But by the 1940s this research had shown definitively that an electric shock only induces ventricular fibrillation if it falls during late systole — in EKGspeak, at the T wave.

Lown’s team arranged to time a shock to the QRS to avoid that, and the synchronize button was born. We act like it’s always been there, but actually, it was conceived of and put there not that long ago.

Lown knew that if we cardiovert at random, even if we’re well-intentioned, our luck will eventually run out.

He then took this insight learned in the practice of medicine, applied it to the wider world, and saw in horror that we had thousands of nuclear weapons — enough to destroy the planet many times over — sitting on hair-trigger alert, poised for irreversible launch within minutes.

Mistakes and random outlier events are inevitable. Sometimes they’re small, comic affairs, like spilling a cup of milk all over the patient transfer forms. Other times, in a flash, they shock a person dead — which is the kind of thing we’re all comfortable in medicine thinking about how to prevent. (That’s why we should push for monitor / defibrillators to improve past this, as has happened constantly over the 75 years since defibrillation was invented: The sync button should be on by default.)

But what about the threat that still carelessly looms over all current and future humans — the completely pointless and avoidable threat of rampant nuclear weapons? I think about this every time the latest tragicomic, unexpected-yet-totally predictable thing happens in the hospital. So did the inventor of the sync button.

An earlier version of this article was published in Emergency Medicine News.

Yep! That’s why it is called the practice of medicine! We humans are not all cookie cutters. The syborgs will be different!

I'm thinking about driverless automobiles when I should be thinking about nuclear missiles.